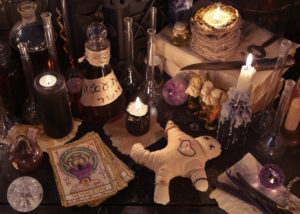

When you hear the word “Voodoo,” what images come to your mind? You might picture hordes of hungry zombies or small, human-shaped cloth effigies stuffed with pins by a vengeful rival or a jilted lover. However, these depictions from pop culture don’t accurately reflect the multitude of spiritual paths followed by practitioners today. As blends of African and European religious influences, each version involves a complex set of doctrines, traditions and practices.

Origins in West Africa

Haitian Vodou and Louisiana Voodoo are the most common variants existing in the Western Hemisphere, but you’ll also find “Vodú” in Cuba, “Vudú” in the Dominican Republic and “Vodum” in Brazil. These terms are all derivatives of “Vodun,” a word from the West African Ewe language that means “spirit.” PBS’s “Wonders” series mentions that Vodun beliefs originated in the Dahomey kingdom, located in what is now parts of modern-day Benin, Nigeria and Togo.

Just as its name implies, Vodun heavily focuses on the roles of spirits among the living and the dead. It views all creation as divine, brought into being by a deity known as Mawu. In addition, other gods and goddesses govern aspects of nature, while supernatural entities protect each clan, nation or tribe. Individual trees, rocks and bodies of water can house their own spirits, and dead ancestors are revered by their living descendants.

New Religions Made in America

With European conquest and the transatlantic slave trade, Africans brought to the Americas carried their original spiritual principles with them. As explained in a 2013 Live Science article, these slaves combined their beliefs with Roman Catholic traditions. Thanks to the “Code Noir,” a 1685 proclamation by French monarch Louis XIV, they were forbidden from engaging in religious practices from their homeland and were forced to convert to Christianity. New arrivals in Saint-Domingue, located in present-day Haiti, complied by adopting the Christian faith.

Fortunately, Catholicism’s reverence of patron saints gave them an ideological structure into which they could integrate Vodun deities and philosophies, giving some Catholic figures alternative or double meanings. This process, known as syncretism, merges disparate traditions to create new belief systems. For example, Ogun is viewed as a deity of justice, medicine, warriors and metalworking and is associated with St. James the Great. Similarly, Maman Brigitte is a protector of gravestones who is usually syncretized with St. Brigid or St. Mary Magdalene.

Why Did Voodoo Get a Bad Rap?

Although forced Christianization contributed to the creation of Voodoo, racism soon led to fear and ridicule of its new spiritual paths. Saumya Arya Haas revealed in a 2011 Huffington Post piece that many leaders in the Haitian Revolution were Voodoo practitioners. As European colonialists lost their foothold on the island in the late 1700s, slave owners throughout the Caribbean and the United States feared that the same could happen to them.

Such worries gave rise to a variety of responses such as legal repression, negative stereotypes and religiously fueled fury against “witchcraft.” True to the human tendency to become fascinated with the forbidden, common misconceptions about Voodoo eventually made their way into popular culture. These included some superstitions that are not even part of these spiritual practices. For instance, zombies come from rural Haitian folk tales of walking dead enslaved by evil sorcerers while “voodoo dolls” may have originated in the British Isles.

Traditions and Beliefs Kept Alive

Despite the mass Christianization of African slaves in the Americas, many found ways to preserve remnants of ancestral beliefs and practices. The multifarious forms that Voodoo has assumed in the United States, the Caribbean and other areas provide spiritual nourishment and hold deeper cultural meanings for their devotees. Additionally, these spiritual paths are testimonies to human resiliency, resistance and survival in the face of oppression.