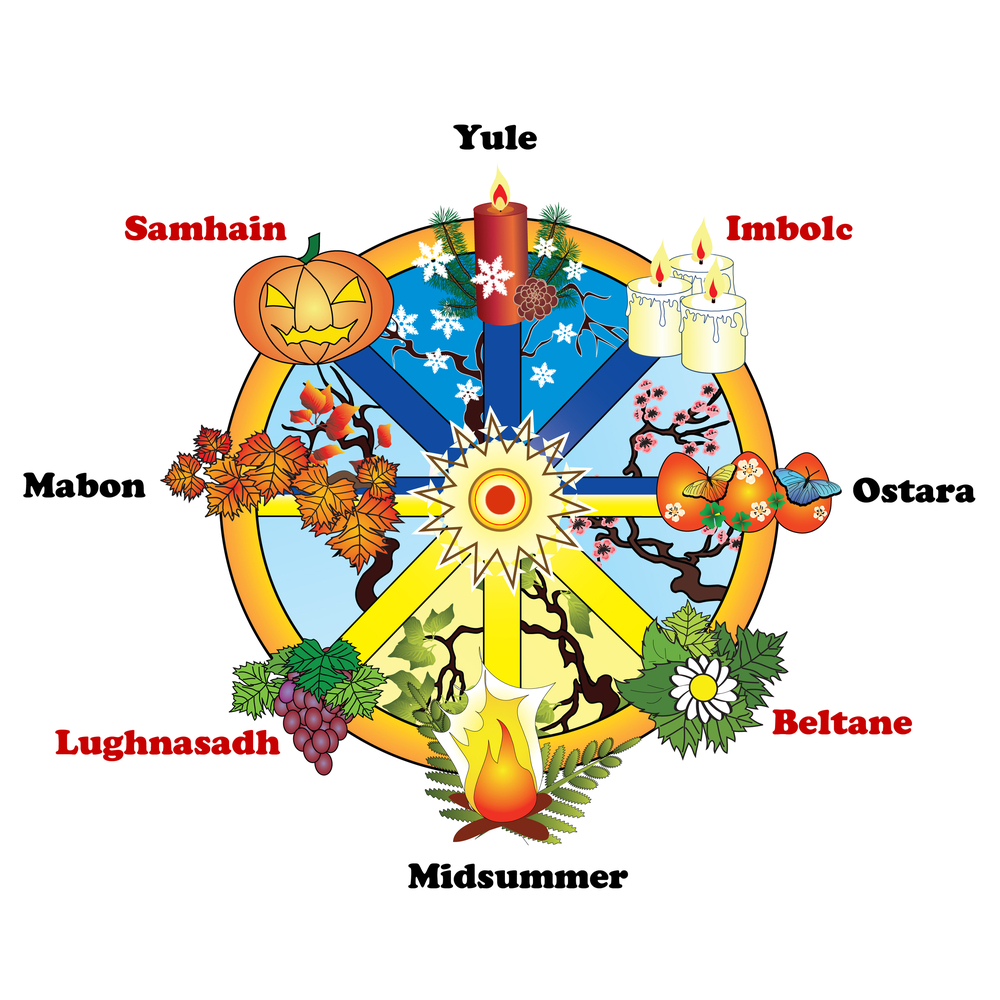

For many people, the traditional year starts in January and ends in December, with various holidays scattered throughout arising from cultural, religious, and national traditions. Adherents to Wicca and other Pagan traditions observe what’s known as the Wheel of the Year, a cycle of festivals based on the year’s solar events in the Northern Hemisphere. Each annual cycle includes eight celebrations of importance to Pagan groups, both ancient and modern.

The Wheel of the Year

The Wheel of the Year can be envisioned as a wheel with eight spokes or a clock with eight equidistant positions instead of twelve. Starting at the top, Yule corresponds to the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. The three, six and nine clock positions correspond to the other annual solar events: the spring equinox, summer solstice, and autumn equinox respectively. The other four parts of the Wheel of the Year are based on the midpoints between each solar event.

Yule (Winter Solstice)

Yule, referenced in some of our most enduring Christmas carols, corresponds to December’s winter solstice, the day with the least amount of daylight. In Wiccan traditions, the Wheel of the Year is centered on the idea of a marriage between the god and the goddess of the god/goddess duality. In Yule, the god is born from the goddess. Yule is often observed with feasts and gift-giving.

Imbolc

Halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox, Imbolc is observed by many Pagans. It typically falls on the first of February, aligning with Groundhog Day. Imbolc is considered the first of three spring-related celebrations, and many make dedications and pledges for the rest of the year.

Ostara (Spring Equinox)

The spring equinox, when day and night are equal, is when many Pagan adherents celebrate Ostara. It is the second of three spring celebrations, and its name is derived from Eostre, a West Germanic spring goddess who also gives us the name Easter. This balance of light and darkness in March is a time of new beginnings.

Beltane

One enduring Beltane tradition is that of the maypole, where merrymakers adorn poles with flowers. Observed in early May, Beltane is the last of the three spring celebrations. In Wiccan traditions, the god and goddess are at their sexual peak here, and he impregnates her at this time.

Litha (Summer Solstice)

Litha marks the midpoint of the wheel and corresponds to the summer solstice in June, the longest day of the year in terms of daylight and the beginning of summer. This is the turning point, and many adherents begin to look toward the rest of the year as a decline. The Wiccan god is at his strongest during Litha.

Lughnasadh or Lammas

As the first of three autumnal celebrations, Lughnasadh or Lammas is observed by Wiccans baking a figure of the god into bread and eating it. This late-summer tradition is done to acknowledge the sanctity of the upcoming harvest. Some Pagan sects celebrate with offerings of the first fruits of their harvest.

Mabon (Autumn Equinox)

The first day of autumn is observed in September and marks the second time when day and night are balanced. Observed as Mabon, adherents often celebrate by giving thanks for the harvest. This is the second of three autumnal observances.

Samhain

Midway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice, many Pagan groups celebrate the lives of the dead. Samhain corresponds to Halloween and the Day of the Dead. Opposite from Beltane on the wheel, this time is when the Wiccan god who has weakened since the summer solstice passes into the underworld.

As the year moves toward the next Yule, the Wheel begins its next rotation. The Wiccan god is reborn to the ageless goddess. Followers begin another turn of the wheel, with seasonal observances and corresponding celebrations. In the Southern Hemisphere, the cycle is shifted by six months to match the solar events there.